The flu game

Running 3:13 at the Valencia Marathon

In 1997, Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls were playing the Utah Jazz in the NBA Finals, a best-of-seven series of games to decide who would become that year’s champions.

The Bulls had won games one and two at home. The next three games were played in Utah, and the Jazz won game three and four, taking the series to a 2-2 tie.

The morning of Game Five, Michael Jordan woke up at 2am with stomach cramps, vomiting and diarrhea, the result of food poisoning, likely from a bad pizza.

His trainers told him he couldn’t play. The media were told he had the flu.

Without their star, Chicago would struggle to beat Utah, who were yet to lose at home in the playoffs that year.

Luckily for Chicago, Michael Jordan isn’t the sit-this-one-out type.

At 5:50pm, he got out of bed, got dressed, and made it to the Delta Center in time for the 7pm tip off.

Shaky, unsteady on his feet, and on the verge of passing out, Jordan went to work.

He played 44 minutes of a 48 minute game, and scored 38 points, including a crucial 3-pointer in the waning moments of the fourth quarter, which put the Bulls in the lead.

They held on to win the game, and won the entire championship two days later in Chicago. If Jordan had stayed in bed, that likely wouldn’t have happened.

Game Five quickly passed into legend. Some rate it as the best game he ever played. Jordan himself said it was “probably the most difficult thing I’ve ever done.”

It became known as The Flu Game.

Five weeks ago, after 14 weeks of near perfect marathon training, I got achilles tendinitis on my left side.

Early efforts to rehab it held promise, and I got through my 15th and 16th week of training with my plan mostly in tact. But then came the unintended consequences.

There are two things you can do when your achilles tendon flares up. You can calmly begin rehab and reduce your paces and mileage, or you can panic.

I’ll let you guess which approach I took.

I immediately loaded my tendon with heavy weight in the gym, doing eccentric calf raises (slow heel drops) and isometrics (holding a heavy weight on tip toes).

This made the tendon feel much better, and I could run pain free after these sessions.

But in immediately jumping to a weight I thought I could handle rather than slowly building up. I managed to piss off the insertion points in my heel, where the tendon joins the bone. That’s two lots of tendinitis for the price of one.

When the achilles tendon insertion points hurt, it’s painful to wear shoes. The heel cup rubs where the tendon meets the bone, and running quickly becomes very sore.

By week 17 I was cross training every other day.

By week 19 I wasn’t running at all.

It didn’t look good.

A marathon block is an act of faith.

You commit to a plan for three-to-five months. You give it your all. 5am starts, evening sessions, an hour of training every day. Two-and-a-half hours on Saturdays.

You bin off vices, watch what you eat. You say no to work drinks and try to get to bed early. You lose weight, log every kilometre, track every data point. You watch your fitness increase. You do the math, calculate optimal paces, carb intake, kit choices.

You run 20 miles before breakfast on half a dozen occasions. You practice fuelling, practice sustained effort, practice suffering. All in order to make it to the start line.

All for the privilege of suffering some more in the hopes of finishing a race.

All with no guarantee of a reward.

Because even if you stay healthy, you aren’t owed a time.

The marathon doesn’t owe you anything.

And if you aren’t healthy. If you fail to make the start line. If you can’t finish the race. That’s it. That’s all she wrote. You have to start all over again, from scratch.

Like an equinox, you only get two chances a year. Miss it, and you’ll be waiting six months for the next one.

My flights were booked, my hotel paid for, but I wasn’t sure I was going to be able to race in Valencia. And if I did, I had no idea if I’d be able to finish a marathon.

Last Sunday, I hauled myself out of my hotel bed at 4:30am, ate breakfast, made coffee, stretched, and got dressed. Then I laced up my race shoes and went to work.

After a madcap dash to grab the phone I left in an Uber (it was that kind of morning), I made it to the start line in plenty of time for the 8:40am gun.

For a week I’d been in my head about what would happen during the race. Would I tear my achilles? Would I fail to finish? Or worse, run slower than last time?

My physio, EJ, told me it was a different challenge now. It wouldn’t be the race I was planning for. But that didn’t mean it was already over. “You never know,” she said.

I had to change the narrative, reframe the story. Being able to run a marathon is a privilege. Just finishing this race with an injury would be a massive achievement.

In the days before the race I started thinking about the Flu Game, about what can happen when all seems lost. If you show up anyway, and try your best.

In the starting pen, I felt calm. I met Kofuzi, a runner I’ve admired for years. Now I was lining up alongside him. No matter what was about to happen, I made it this far.

Only 26.2 miles to go.

Go time. The Star Wars theme played for some reason. The Spanish announcer embraced hyperbole. Then the gun went off, and thousands of runners surged forward.

I set out at a conservative pace. I’d been able to hold a 4:45/km pace at a very easy heart rate in training, so I started there for the first kilometre, when everyone was still helpfully bunched together and there was no temptation to push too hard.

When that felt okay I locked in at around 4:25/km, and stayed there, with no issues, for the first half of the race. This had been my training pace for my longer intervals, so it felt very comfortable. I took a gel every 20 mins and sipped water from my hand bottle.

Hold this pace, and I’d be looking at a sub 3:10 marathon.

At 10am, the city started to heat up. With a dull, constant pain coming through the achilles now, I popped two paracetamol and passed the half in 1:33.

What followed was the most difficult part of the race.

Back in 1997, Jordan, fatigued from his first half efforts, rode the bench during the third quarter.

Between the half and the 30km mark — the third quarter — the calf on the right side, which was doing most of the work compensating for the left, started to seize up.

The left, which was already junk, then had to carry more of the load, and quickly seized up, too. I wasn’t cramping, but I was very stiff, and the range of motion in my ankles was deteriorating by the kilometre.

My pace slowed by 10 seconds per KM, then 20. My lungs were fine, my heart rate high but within normal range (this usually happens in races, especially with the heat), I simply couldn’t work my legs. I plenty in the tank, but nothing in the tyres.

The sub-3:10 was slipping from my grasp.

I cycled through my mantras. I have one where I imagine a thread attached to the back of each knee, pulling my legs backward. It’s a little trick I use to engage my glutes when I run. I chant “pull, pull, pull” to myself with each step.

Another is “you don’t need to go any faster than this.”

The pain hit a 5/10 and stayed there.

My left achilles tendon had no spring, and my right soleus was a rock.

In order to move more efficiently, I started heel striking. I normally land right on my toes, so my leg muscles took a moment to adapt, but even if I wasn’t moving any faster, it provided some respite to my tendon.

As I finally hit the 30km mark, I pulled my Airpods from my belt and slipped them into my ears.

This was the moment I’d been waiting for.

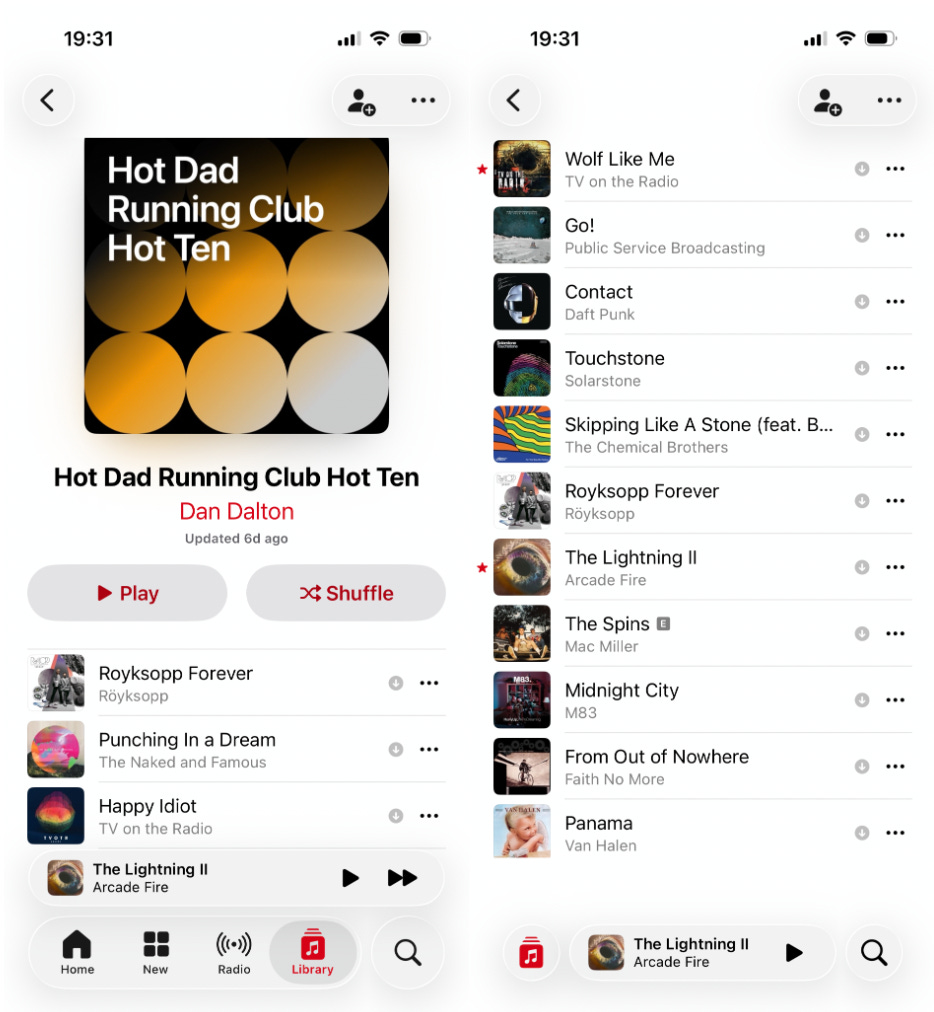

I have a “fast 10km” playlist that I’ve trained with for the past 20 weeks, every interval session, every bit of speed work during a long run.

It tells my brain it’s time to go to work. It’s like post-hypnotic suggestion. Or Pavlov. My heart rate increases, my legs turn over faster, I hold my pace longer.

In short, it hypes me the fuck up.

I knew if I used it in Valencia during that third quarter slump, that I’d run out of steam before the end. I had to wait. I had to time it just right.

Just like Jordan recouping in the third quarter before rallying in the fourth and bringing it home, I had to wait for the whistle. My time would come.

At 30km, when I hit play, I didn’t suddenly speed up. In fact, I was still slowing down. But now I wasn’t desperately waiting for the kilometres to tick over. I was locked in.

The other thing that happened was I passed 32km under two hours thirty. I now knew if I could hold on and run the last 10km in under an hour, I’d beat my London time.

A PB wasn’t just possible. It was probable.

More than that, if I was doing my maths right, a sub-3:15 was still on.

Let’s fucking go.

I alternated heel-striking with my usual gait. I kept swallowing gels and salt pills. I filled my hand bottle with water from volunteers. I stuck to the tangent line like glue.

I’d slowed to around a 5-minute pace and was being passed every few seconds. But I fought to stop this getting to me. All I had to do was keep moving. Just keep moving.

I might be struggling physically, but my mental game was bulletproof.

In training I’d done a 22-mile long run on a treadmill to avoid flaring up my achilles on hills. I’d done 2 x 2:30 stints on an elliptical when I couldn’t run long. I knew how to sit with discomfort, monotony, pain. I’d trained for this. I can take it.

Instead of focussing on being passed, I started noticing the runners I was passing. No matter how much pain I was in, there were people having worse days.

I adopted a new mantra. Between bouts of “pull, pull, pull,” and “you don’t need to go any faster” I started thinking “you’re moving better than them.”

(I sincerely hope those runners finished the race and were okay).

Towards the end of the race, when they stop marking the kilometres, the terrain shifts and you begin a long gradual downhill. The crowds were suddenly denser and louder.

At 3 hours, I pulled out my last gel and opened it, but only put a little in my mouth before I cast it aside, trying to trick my brain into thinking I was taking on fuel.

I was doing everything I could think to get through the race.

A 900m marker appeared. Then the 800m marker. We were in the home stretch. The phantom coxswain on my shoulder resumed his chant:

Pull! Pull! Pull!

The road turned blue as we veered off the street and onto a temporary surface towards the finish at the City of Arts and Sciences.

Then came a steep downward ramp where the course presumably goes down a long flight of stairs. I let it take me, bounding down it without thought for my quads.

Pull! Pull! Pull!

My legs were screaming. But my heart and my lungs were running the show now, and they’d barely been tested.

I gathered myself at the bottom of the ramp, flowing with the torrent of runners around me, then pushing again in the last few hundred metres, closing in a sprint.

Pull! Pull! Pull!

Seeing the camera at the finish, I raised my hands in victory Vs and used every ounce of energy I had left to stop wincing as I powered across the line.

I finished in 3:13:33. An 18-minute PB.

They call that a Flu Game.

You just never know.

I couldn’t walk after the race. I could move, but it wasn’t technically walking. My ankles couldn’t flex. Everything hurt.

I hobbled to collect my medal. And then hobbled to meet my wife and my friend, Tom. I was welling up from the pain and the effort.

A runner from Seattle noticed and reached out. “That was hard,” he said. We laughed about the rain back home, how this weather was out of our comfort zones. He made me feel better. I wish I’d got his name or bib number. Thank you for the kindness.

I collected a bottle of bright red Powerade I knew I wouldn’t be able to stomach, and a banana that I would. I looked at my phone and asked my wife to drop me a pin. I had no idea where I was. Race organisers always want you to walk so far at the finish.

My brother text me a picture of my time. “You’re a fucking beast,” he said.

I thought about my son, that when he asked if I ran fast, I’d be able to say yes (what he actually asked me, the next day, is if I won, which is both hilarious and sweet).

I collapsed into my wife like Michael Jordan into Scottie Pippin’s arms, totally spent.

Tom (who had run a PB of his own in 2:44:33) and I shared a joke I don’t remember.

We made our way, excruciatingly slowly, to a bar to grab a beer. Apart from my legs, I felt better than I had after each of my 20-mile long runs.

Over the past 20 weeks I built a massive engine. An engine so big that even an injury didn’t stop me. So finely tuned I could be in that much pain and still run a massive PB.

When things don’t go perfectly, when the story isn’t going the way you planned, you can reframe the narrative, re-write it. Come at things from a different angle.

And if you prepare as best as you can. If you commit, stay consistent, keep showing up — even when that means doing 22-mile long runs on a treadmill or spending over two hours on an elliptical — you can surprise yourself.

And if you’re deep in the third quarter, suffering and wanting to stop and lie down, just think “flu game.”

Or, failing that, put in your AirPods and go to work.

More tangents.

Here’s my Strava if you’re into that sort of thing.