Running to live, with Nicholas Thompson

Thoughts on life, death, and "The Running Ground"

It’s almost exactly two years since my father died. The death of a parent isn’t something you ever move on from, really. You grieve, and time passes. That’s all.

Grief is an endurance sport. You just find ways to keep moving forward.

We tend to remember the good things. Or try to. Dad wasn’t without his flaws. He was a love addict who married five times, and died, surrounded by bike parts he was either hoarding or attempting to flog on eBay, without a penny to his name.

He was also brilliant. Charming, well read, worldly. A Facebook thread my brother started announcing his passing had over a hundred comments.

The sentiment was nearly identical in each: the nicest, kindest man I’d ever met.

There were stories of how he went out of his way to help people. His former students said how he’d affected their lives, some of whom he’d kept in touch with for decades.

I read these messages with pride and awe, but also jealousy. This was my Dad. My pain. There was resentment wrapped up in there, too. And regret.

Grief is all the emotions at once, jockeying for position in your chest.

You learn a lot about a parent when they die. Not all of it good. Alongside the aforementioned bike parts, old phones, and obsolete charges were boxes of papers.

I found out he was a member of MENSA, which he’d never talked about, and that he was in a great deal of debt. He’d taken out loans in the thousands of pounds as recently as six months before he died. He didn’t leave a will.

I also found the beginnings of several books, most of them anecdotes about cycling, most of them false starts. By publishing a novel, I’d achieved a goal of his without ever knowing it. He never mentioned it. He just told me how thrilled he was. He meant it.

He was my biggest fan, and my biggest trauma.

He left us while Mum was pregnant. Running from responsibility, or the idea that he might fail. Or both. It’s possible he simply didn’t know how. His dad had died when he was very young. Perhaps he didn’t have the instructions. I never got to ask him.

I might not have been born yet, but I felt it. It has informed much of who I am. Fear of abandonment. Feeling like I need to prove myself worthy of love.

It’s the reason I’ve achieved so much. It’s the reason I haven’t always enjoyed doing so.

Thanks in large part to the efforts of my mum, who deserves a medal or two, and in spite of my Dad’s lack of organisation and timekeeping, my brother and I always spent time with him growing up.

Dad was easy to love. He was generous with his praise, with hugs, with compliments. He’d always kiss me on the cheek when we met and parted. He was very funny, a good hang, and a great cook. He took us hiking and rock climbing and cycling.

It’s easy to believe all the things the people said about him. That’s who he was.

He was also difficult. He was navigating traumas of his own, most of which he never got out in front of. He was unfaithful to each of his wives. When relationships got difficult he would find someone new, jump ship rather than deal with difficult things.

He lost his hearing in the last decade of his life. He refused to wear his hearing aids — likely due to embarrassment — and couldn’t read lips. Sometimes he would take guesses at what you said and miss the mark by a mile.

Sometimes he would concentrate very intently, picking up what he could.

In those moments, to converse with him was to speak to someone fully present. I think that’s what people were responding to. Despite not being able to hear much of anything, he gave the impression of someone who really listened.

I usually saw him a couple of times a year, but I texted with him every week. We would talk about outdoor brands and books he wanted me to read and whether my son was ready for a bike yet (he’d just learned to walk).

I didn’t let him visit as much as I might have. He could be hard work in person. But he was excellent in writing. And he’d always reply.

When I miss him now I usually miss his hugs. But the amount of times I’ve thought “I should text Dad about this” before catching myself. I still do this now, two years later.

Grief is an endurance sport.

A couple of weeks ago I read an essay by Nicholas Thompson in the Atlantic that affected me deeply. It was an excerpt from a new book. I ordered it immediately.

The Running Ground is about life and death. About fathers and sons. About success and failure. It’s part memoir, part manual for living, for not giving in to middle-age decline. And yes, it’s also a book about running.

There are a lot of books about running. But The Running Ground stands alongside Murakami’s What I Talk About When I Talk About Running as one of the great works of literary writing about life through the lens of running. It’s a remarkable achievement.

And unlike most books about running, The Running Ground is one I’d recommend to any reader. This is a story about what we choose to live for.

Thompson, a former editor and current Atlantic CEO, writes with eloquence and tenderness about his relationship with his father, who introduced him to running, and a fair amount of self-deprecating humour and modesty about his own exploits.

Along the way, he also recounts the stories of a series of runners he admires, each of whom have had to overcome something to keep running — addiction, incarceration, institutional sexism, degenerative disease.

But The Running Ground isn’t a heavy volume. It’s struck through with joy and love.

It’s a book that has deep affection for its subjects, but also a deep understanding of the absurdities of both life and being someone who chooses to run marathons.

(Pheidippides, for his part, was just doing his job.)

This balance of affection and humour is never more effectively woven than in the anecdotes about his father.

Thompson extends more empathy to his old man than he ever offers himself. Perhaps this is simply the nature of the long distance runner — we like to beat ourselves up.

Scott Thompson was, by all accounts a brilliant man who enchanted everyone he encountered, including a young Senator from Massachusetts, one John F. Kennedy.

His shadow casts a long silhouette.

The Running Ground is also a book about grief. Lying beyond the reach of humour, glimpses of childhood reverence are coloured with more painful memories of his father’s later years, as he slipped into financial trouble, sex addiction, and self-exile.

In his efforts to understand his father’s decline, and avoid it, Thompson details how their lives unfolded in sometimes heartbreaking mirrored images of each other.

In the 1980s, his father was diagnosed with AIDS, then told that he didn’t have it after all. When Thompson found a lump in his neck at age 30, an initial biopsy showed the tumour was benign, only for a panel of doctors to reverse that decision. It was cancer.

Where Thompson got a break — landing an editorship at the New Yorker he thought he’d missed out on, thanks to a chance encounter at a party — his father got a closed door, never learning how close he came to a plum role in the Reagan administration.

These sliding doors moments defined each man’s life, pushing one to spiral into excess and the other to strive for excellence.

They caused one to hang up his running shoes and the other to become one of the best age-group runners in the US, and a record holder in the 50k.

Thompson’s father believed a man began to decline after he turned 40. That belief shaped his response to setbacks. It shaped his narrative, and that narrative shaped his world. At 40, he set about fulfilling the decline he knew was coming.

This determination is the core thesis of The Running Ground.

The determination to destroy yourself, and the determination not to. To run and hide or to run and live. To get laid or to get faster.

When the book does talk about running, it doesn’t offer quick fixes or magic formulas.

Thompson preaches the basics, the kind of methods runners have followed since the advent of the modern marathon: consistent high mileage, lots of easy running with a touch of speed work, repeated week in, week out, over years.

Part of the explanation for Thompson’s prodigious achievements is hard work. But it’s also partly due to talent.

He was already fast when, in 2018, Nike tapped him for a training program that paired elite coaches with ‘regular’ runners to help them get faster.

He was given access to Nike’s secret weapon, the Zoom Vaporfly 4%, a shoe which has re-carved the running ground over the past 8-years, bringing space-age foams and carbon plates into the realm of mere mortals.

He was running 2:43 marathons so consistently, a runner at his track club named him “Mr Two-forty-three,” a name Thompson hated, but felt wasn’t entirely unfair.

He was eventually able to run 2:29 marathon, at age 44. He went on to break the American record in the 50k for the 45-49 age group.

I reached out to Thompson via email, and asked why he wanted to write this book. He told me he wanted to understand why he had gotten faster in his forties.

“It had less to do with my training and more to do with the way I mourned my father and how I dealt with a cancer scare,” he said. “My introspection led me to realise that what makes people fast, or slow, can be buried deep inside.”

When Thompson turned 40, he started to believe that not only could he not decline, he could improve. He was determined to get faster, and devoted himself to doing so.

The message is simple: Life, and running, is about what we set our minds to. What we choose to believe about our abilities, and how that shapes our actions.

Not everyone can run a sub 2:30 marathon.

But anyone can improve, if they devote themselves to doing so.

When I spoke to Thompson, he was in good spirits. It was publication week, and he was tapering for the New York Marathon, channeling all his spare energy into book promotion. I asked him about his niggles ahead of New York.

“I have a slight bit of tendinitis in my knee,” he told me. “That’ll be fine.”

“But I have a very weird problem with my resting heart rate, which has been 10-15 beats above normal for ten days, and my HRV, which has been 10-15 ms below normal. I’m not sure what’s going on, but it’s not going to help on Sunday.”

We spoke about running shoes, if he obsesses over them, as I do — at any one time I have 3-5 tabs open in my browser researching my next pair, looking for the best deal. I can talk about foams, plates, and stack heights all day.

“I’m a 95th percentile obsessive, not a 99th,” he says. “I do tests before races to see which shoe seems to be working the best.”

“I’ll go to a track with my HR monitor and a power meter and alternate running miles at race pace in different pairs to see which helps me move most efficiently.”

I also asked Thompson why runners are so prone to getting philosophical about running, in a way that, say, footballers don’t seem to be about football (either the English version, which is played with feet, or American version, which isn’t).

“It’s a sport that encourages introspection,” he says. “You’re out on your own, in the open air, and your mind can wander in a way it doesn’t if you’re rushing the quarterback on 3rd and 7.”

“Also: runners tend to be nerds. How many kids on your high school hockey team studied philosophy, and how many kids on the high school cross country team did?”

It’s clear that we went to different kinds of high school. But I get his point.

It’s hard to run 20 miles before breakfast without considering the why of what you’re doing. Without weaving it into some grand narrative framework that justifies itself.

Otherwise you’re just running 20 miles before breakfast.

And without deep thought and rationalisation, that might not seem entirely sane.

The Running Ground is a book that asks as many questions as it answers.

It prompted long-run levels of introspection as I listened to it via audiobook. I thought about both my dads. About my relationship with my running, with my personal and professional life. With what I’m living and running for.

That’s what a great book does. It holds up a series of lenses and says, “what if you look at things this way? Is that better, or worse? Better, or worse?”

Finally, I asked Thompson about what’s left. About what remains once the records are broken, once the body fades, when you can no longer push further, run faster, PR.

What will running mean then?

“I probably won’t PR again in anything. The hard thing will be if something flips and I just can’t be fast at all. Then I’ll probably stop racing.”

“But I hope to be able to run from my mother’s house, near Acadia National Park, up to the top of nearby Brown Mountain, until I’m at least 70.”

This is the final lesson of The Running Ground.

If you take away the GPS tracking, the chip times, the super shoes. If you take away the ego, the Strava kudos, the records, then simply lacing up your shoes and putting one foot in front of the other — just keeping going — is an achievement.

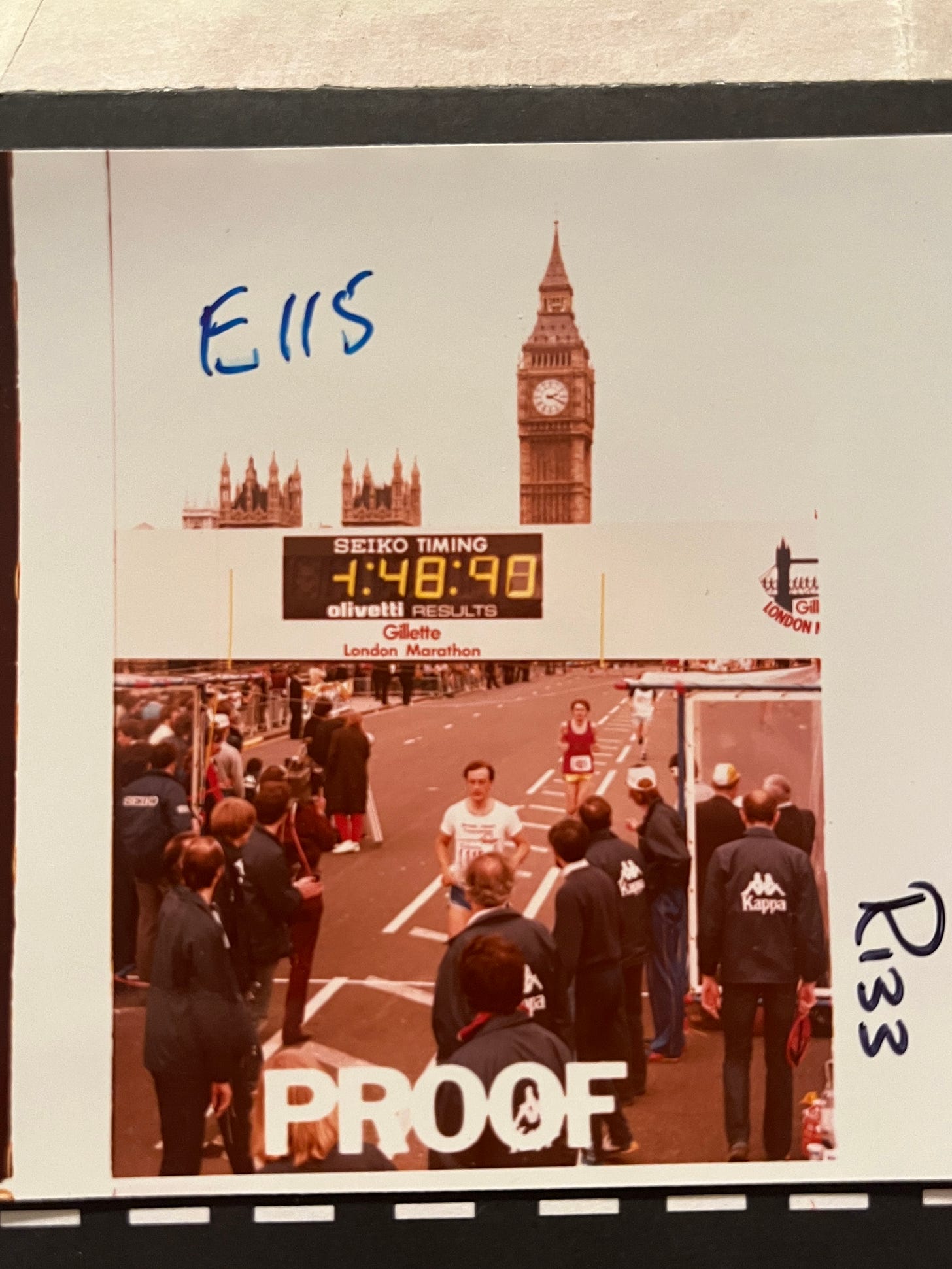

My Dad’s marathon career was short. One race: The 1982 London Marathon. Among his papers was a picture of him crossing the finishing line.

I beat his time on my first try. He would have been thrilled.

I don’t know why he stopped running, but I know he indulged in a few years of rich living after that, resulting in a heart attack in the early ‘00s.

He took up cycling as part of his recovery, a sport he’d loved as a boy, and never looked back. When he died he was one segment shy of circumnavigating Britain

He didn’t get me into running, the dad who raised me did that. I stopped because I didn’t think I was made for running. I was standing in my own way.

I found it again, at 40, after a few hard years of my own. That was the year before he died. My son had just been born. I chose to stay. I was always going to stay.

Dad wasn’t ready when my brother and I were born. But after that heart attack, he changed. He took stock, took early retirement, moved to a quieter part of the country, with flatter roads and better cycling. He checked in more often.

Anyone can improve, if they devote themselves to doing so.

He wasn’t without his flaws. Ask any of his wives. But he found a strength I didn’t understand until I was a Dad. No matter what he was struggling with, no matter his demons, or money troubles: He showed up. Rain or shine, he kept showing up.

Shortly before he died I told him I wasn’t sure if I’d like to run a marathon.

His advice was succinct: “You have to want to do it,” he said.

Parenting and running are similar that way. You have to want to do it.

The Running Ground by Nicholas Thompson is out now.

Read his essay, “Why I Run,” in The Atlantic.

Follow him on Bluesky and LinkedIn.

For more Tangents, read my essay about running as a father and a son here.